Drop down header

Monday, 6 October 2014

Friday, 12 September 2014

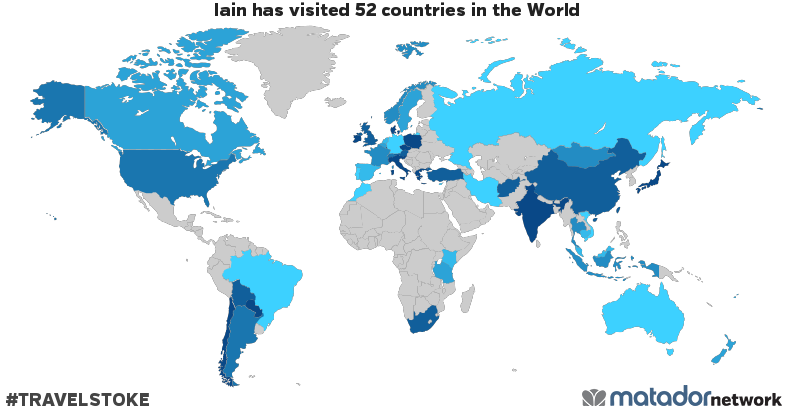

+1 Paraguay

Iain has been to: Afghanistan, Andorra, Argentina, Australia, Austria, Belgium, Bolivia, Brazil, Cambodia, Canada, Chile, China, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Fiji, France, Germany, Greece, Guernsey, Hong Kong, India, Indonesia, Iran, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Kenya, Luxembourg, Malaysia, Monaco, Mongolia, Morocco, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Paraguay, Poland, Portugal, Russia, Singapore, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Tanzania, Thailand, Turkey, United Kingdom, United States, Vatican, Vietnam. Get your own travel map from Matador Network.

Thursday, 14 August 2014

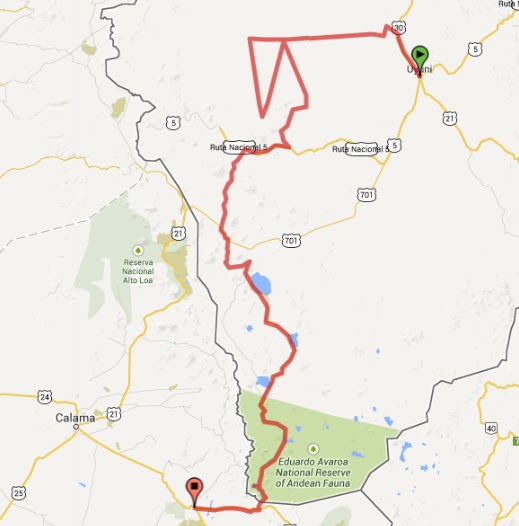

Leg 9 - San Pedro de Atacama to Sucre

Route summary: San Pedro de Atacama, Calama, Iquique, Calama (again), Pica, El Gigante, Arica, Putre, Oruru, Sucre, Potosi, Sucre.

Days: 53

Zero mileage days: 29

Distance (point to point): 529km

Distance (driven): 3,954km

Inefficiency factor (Driven/P2P): 7.48

Avg. speed: 75km/day

Zero mileage days: 29

Distance (point to point): 529km

Distance (driven): 3,954km

Inefficiency factor (Driven/P2P): 7.48

Avg. speed: 75km/day

Click here for detail.

After the ride from Uyuni I spent the first three days recovering, putting my panniers back together again (which involved taking them apart first) and putting my bowels back together again [1]. After 3 days I need to move hostel as they don't have any space - I'm assuming it's down to the fact that they had prior bookings and not because I've been monopolising the common area in the centre of the hostel with my dismembered panniers. So I move to another hostel down the road and my sleep pattern goes from, going to bed at 9 and up at 7 (because that's when the French girls I'm sharing the dorm with sleep), to going to bed after midnight, usually having consumed a fair quantity of beer and wine, and emerging the next morning around 9:30 in order to catch the end of breakfast.

After the ride from Uyuni I spent the first three days recovering, putting my panniers back together again (which involved taking them apart first) and putting my bowels back together again [1]. After 3 days I need to move hostel as they don't have any space - I'm assuming it's down to the fact that they had prior bookings and not because I've been monopolising the common area in the centre of the hostel with my dismembered panniers. So I move to another hostel down the road and my sleep pattern goes from, going to bed at 9 and up at 7 (because that's when the French girls I'm sharing the dorm with sleep), to going to bed after midnight, usually having consumed a fair quantity of beer and wine, and emerging the next morning around 9:30 in order to catch the end of breakfast.

I ascribe the change on the fact that at the second hostel I met a bunch of English cyclists, who were initially recovering from a long ride into San Pedro and latterly bracing themselves for the hard ride to Uyuni. I did manage to see some of the sights in the San Pedro area though. The Valle de la Luna was beautiful (large dunes and strange shapes formed in the rocks from wind and water erosion) but I think had been over-hyped beforehand so it didn’t quite knock my socks off as anticipated, although on the way I nearly strayed into a minefield which added a frisson of excitement. There were lots of other trails through canyons in the area which were fun on the bike (until I got stuck axle deep in soft sand), nearly as pretty as Valle de la Luna but without the coach-loads of other people.

Another afternoon I hired a bicycle and rode out to Laguna Ceja with two of the cyclists. It’s a lake with a high enough salt content that you float in it, like the Dead Sea, but was bitterly cold so didn’t stay in it for long. It was for the most part a fairly shallow pool (about thigh deep), but in one area the ground suddenly dropped away so that, even though the water was incredibly clear, there was no way to see the bottom.

Then there was an early morning start to go to the Geysers de Tatio, the highest geyser field in the world, and very cold when we arrived there pre-dawn (I decided to go on a tour as I’d heard the road was in pretty awful condition, although it didn’t seem too bad as I managed to sleep most of the way there). Some very large geysers, a stunning range of colours from the various minerals, and at dawn the most ethereal feeling as you walked through clouds of smoke, albeit with coachloads of people doing the same thing. In another attempt to educate myself about the stars of the southern hemisphere, I went on a sky-viewing tour (the world’s biggest ground based telescopes are near San Pedro), which was interesting, but I think the tour in La Serena was better (and warmer), although that one didn’t have Pisco and wine afterwards.

Then there was an early morning start to go to the Geysers de Tatio, the highest geyser field in the world, and very cold when we arrived there pre-dawn (I decided to go on a tour as I’d heard the road was in pretty awful condition, although it didn’t seem too bad as I managed to sleep most of the way there). Some very large geysers, a stunning range of colours from the various minerals, and at dawn the most ethereal feeling as you walked through clouds of smoke, albeit with coachloads of people doing the same thing. In another attempt to educate myself about the stars of the southern hemisphere, I went on a sky-viewing tour (the world’s biggest ground based telescopes are near San Pedro), which was interesting, but I think the tour in La Serena was better (and warmer), although that one didn’t have Pisco and wine afterwards.On one night we heard about a desert party that was happening, so around midnight a group of us walked out of town and met clusters of people heading to the same destination but with a clearer idea the destination, which was helpful as otherwise we’d never have found it. It was a fairly basic set up in a small tree-lined clearing; a table with the DJ’s decks, a couple of speakers, a small bar and a fire in a half oil-drum. A fun night, albeit very cold, and a beautiful walk back into town and the hostel in the pre-dawn stillness.

After fixing the panniers I decided that I probably needed a bit of a makeover as well so the beard went (this time via a number of different styles) and a haircut. A similar response as in Santiago – the young woman who worked at the hostel asked me when I arrived and it took a good couple of minutes for her to realise it was me and that we’d spoken on numerous occasions.

After a couple of attempts the cyclists left to head up the hill to Bolivia and the next day I left. The next stop was Calama, only about 100km away but my laptop was still playing up and apparently it had the only Mac store in northern. Calama didn’t have a great write-up in the guidebook, but it seemed a nice enough town, and I was able to sort out a bunch of things that the tourist-oriented town of San Pedro wasn’t able to help with (bike clean, additional straps for my panniers, replacement indicator and eventually my laptop fixed). The clutch was also being very stiff and when I went to get the replacement indicator I asked if they had any idea what might be causing it – I was concerned that there was some delayed damage from the crash at the beginning of the trip or I’d done something when I’d dropped the bike on the way from Uyuni. Wheeled the bike into the garage and one of the guys looked at the clutch lever, where the cable goes into the gearbox, squeezed the lever closed, then rotated the hand grips round. I have heated grips (which aren’t working at the moment) and where the cable joins the grip, the rubber is thicker. Over time the grips had rotated round and the thicker rubber was obstructing the clutch handle. Slightly embarrassed, but grateful it was something so simple, I thanked them and wheeled the bike away.

The laptop was going to take at least 4 days to fix - it was diagnosed with having a knackered hard drive and a battery on its last legs and they needed parts to be sent up from Santiago. So I decide to head up to Iquique and wait for it there (having to come back would mean that I would be able to ride both the desert road and the coast road between Calama and Iquique.

The laptop was going to take at least 4 days to fix - it was diagnosed with having a knackered hard drive and a battery on its last legs and they needed parts to be sent up from Santiago. So I decide to head up to Iquique and wait for it there (having to come back would mean that I would be able to ride both the desert road and the coast road between Calama and Iquique.After a few false starts I eventually leave Calama in the mid-afternoon and ride up past the massive copper mine at Chuquicamata (it had been closed for the week to tours) where the slag heaps from the mine waste rival the mountains in size over a pass and down into the desert, a perfectly straight road which is paralleled by half a dozen large power lines, presumably to support the copper production process when the wind farms in the area aren’t generating enough electricity.

The ride up through the desert in the late afternoon as the sunset was beautiful and didn’t get as cold as I’d imagined. Although the last 60 kilometres or so were unpleasant, my dipped headlight had just blown so I was either on full beam or using the fog lights I’d fitted and then hit very thick fog (first precipitation on the visor since Valparaiso). But then the road dropped out of the clouds and suddenly the city of Iquique appeared, at the bottom of a 500m high cliff which the road tracked down. Into the hostel, park the bike, meet a friend from San Pedro and have a barbecue. Not a bad day.

Spend a couple of days site seeing including visits to Humberstone, [2], a look around a replica of the Esmerelda [3] and the town (which had some picturesque parts as well as a beach and some very large sea lions and pelicans that hung out near the roadside fish market. And some more bike admin – including getting a replacement spark plug (I’d found out that the spare I was carrying was the wrong type) and some new bulbs. It was soon time to head back to Calama (I’d estimated that my laptop would be ready) and was heading down the coast road to Tocopilla when I bumped into one of the cyclists from San Pedro (after a few days he’d decided that his narrow tyres weren’t going to be able to cope with the deep gravel and so had decided to take an alternate, tarmac route to La Paz). He persuaded me to head back to Iquique so after lunch I turned around and took a route back to Iquique through the desert, arriving just before him and then had a couple more days relaxing in the hostel by the beach. I’d also discovered that my laptop probably wasn’t going to be ready until early the next week so there was no rush to get back to Calama anyway.

So, after the weekend, I made my second attempt to leave and I went back to Calama on the coast road. The road tracks the narrow strip of land a little above sea level with the ocean on the right (west) and then ochre coloured mountains rising sharply up to about 500m on the left – it did feel like you were on the edge of a continent, and it wouldn’t take much to be nudged into the sea [4].I arrived in Calama just in time to pick up my laptop before the shop shut. I then found out that there was a tour to the Chuquicamata mine the net day in the afternoon, so stayed in town for an extra night. The mine trip in the afternoon was fascinating, I’m going to write more about it [here] as I think the comparison with what I saw in later on in the same leg in Bolivia was quite telling.

So, after the weekend, I made my second attempt to leave and I went back to Calama on the coast road. The road tracks the narrow strip of land a little above sea level with the ocean on the right (west) and then ochre coloured mountains rising sharply up to about 500m on the left – it did feel like you were on the edge of a continent, and it wouldn’t take much to be nudged into the sea [4].I arrived in Calama just in time to pick up my laptop before the shop shut. I then found out that there was a tour to the Chuquicamata mine the net day in the afternoon, so stayed in town for an extra night. The mine trip in the afternoon was fascinating, I’m going to write more about it [here] as I think the comparison with what I saw in later on in the same leg in Bolivia was quite telling. Back on the bike the next morning and north through the desert road again, this time in daylight and so I was able to stop off to look at some geoglyphs (there seem to be loads scattered through the desert). The destination for the day was Pica, an oasis town famous for its fruit, particularly the limes used for making Pisco Sours although my favourites were the mangos. The plan the next day was ambitious, a mirador, dinosaur footprints, a radioactive mud bath, the largest geoglyph of a human before sleeping by the Pacfic Ocean. As it was I wasn’t very successful, the mirador was wasy to find, the dinosaur footprints less so. Then a great, albeit longer than anticipated, breakfast, a chance encounter with some Chilean bikers at a petrol station [5] and a worse road than expected, it was lunchtime in Mamina where I found the mud-baths closed for the day (not sure why, they said something about high winds being a problem) so had to settle with a normal hot thermal bath.

Back on the bike the next morning and north through the desert road again, this time in daylight and so I was able to stop off to look at some geoglyphs (there seem to be loads scattered through the desert). The destination for the day was Pica, an oasis town famous for its fruit, particularly the limes used for making Pisco Sours although my favourites were the mangos. The plan the next day was ambitious, a mirador, dinosaur footprints, a radioactive mud bath, the largest geoglyph of a human before sleeping by the Pacfic Ocean. As it was I wasn’t very successful, the mirador was wasy to find, the dinosaur footprints less so. Then a great, albeit longer than anticipated, breakfast, a chance encounter with some Chilean bikers at a petrol station [5] and a worse road than expected, it was lunchtime in Mamina where I found the mud-baths closed for the day (not sure why, they said something about high winds being a problem) so had to settle with a normal hot thermal bath. All this had made me later than planned so it was getting dark as I arrived at El Gigante. After watching the sunset I was pondering where I’d sleep. I’d asked in the previous town if there was a campsite but they didn’t know of one and I was keen not to stay in an (expensive) hotel. I also wanted to see El Gigante in daylight, but if I went to the closest town the return trip the next day would add 30km and I was concerned about my ability to reach Arica (the next petrol station) as it. And so I thought, why not just camp where I was. It was quiet, just under a kilometre off the main road and I was guaranteed a good view the next morning. So I parked the bike in the penumbra of the lighting in the carpark and set up my tent – the pegs wouldn’t hold in the very soft sand, so I made a series of ties and “pegged” the tent out with some large stones I found, had supper, read some of my book and headed to bed under the watchful gaze of El Gigante. An early start the next day, I wanted to be up and have the tent down before anyone arrived and also to get to see El Gigante as the sun rose behind him.

All this had made me later than planned so it was getting dark as I arrived at El Gigante. After watching the sunset I was pondering where I’d sleep. I’d asked in the previous town if there was a campsite but they didn’t know of one and I was keen not to stay in an (expensive) hotel. I also wanted to see El Gigante in daylight, but if I went to the closest town the return trip the next day would add 30km and I was concerned about my ability to reach Arica (the next petrol station) as it. And so I thought, why not just camp where I was. It was quiet, just under a kilometre off the main road and I was guaranteed a good view the next morning. So I parked the bike in the penumbra of the lighting in the carpark and set up my tent – the pegs wouldn’t hold in the very soft sand, so I made a series of ties and “pegged” the tent out with some large stones I found, had supper, read some of my book and headed to bed under the watchful gaze of El Gigante. An early start the next day, I wanted to be up and have the tent down before anyone arrived and also to get to see El Gigante as the sun rose behind him.

Then on the road north. At the turn off to Pisagua there was a café and I stopped there for breakfast and asked if there was a petrol station in Pisagua, or on the road before Arica. The answer to both was no, but the waitress said that I could buy some fuel from them. So I set off for the coast, with a final ride down the road as it zig-zagged down about 400m altitude in long traverses and passed soaring vultures. Pisagua itself is a small town clutching to the coast at the bottom of another big hill. The location means it seems to be waiting to be wiped off the earth by an earthquake and tsunami combination, and the town, although has some attractive buildings, has seen better days and doesn’t look like it would put up much of a fight if the ocean decided to reclaim the land. Back from Pisagua I bought some fuel from the café and then continued north, through the desert and then down and up two large valley systems before arriving in Arica in the late afternoon and meeting up with the cyclist and some new friends from Europe and Australia.

Then on the road north. At the turn off to Pisagua there was a café and I stopped there for breakfast and asked if there was a petrol station in Pisagua, or on the road before Arica. The answer to both was no, but the waitress said that I could buy some fuel from them. So I set off for the coast, with a final ride down the road as it zig-zagged down about 400m altitude in long traverses and passed soaring vultures. Pisagua itself is a small town clutching to the coast at the bottom of another big hill. The location means it seems to be waiting to be wiped off the earth by an earthquake and tsunami combination, and the town, although has some attractive buildings, has seen better days and doesn’t look like it would put up much of a fight if the ocean decided to reclaim the land. Back from Pisagua I bought some fuel from the café and then continued north, through the desert and then down and up two large valley systems before arriving in Arica in the late afternoon and meeting up with the cyclist and some new friends from Europe and Australia. There’s not a great deal to see in Arica, but enough to keep me entertained for a few days. I went a little out of town to visit a museum on the site of where the world’s oldest mummies were found which was interesting, although the displays of the mummies themselves was a little macabre [6]. Barbecue in the evening and an attempt at making Terremotos, the latter required some work as the wine used to make isn’t particularly easy to find – it didn’t help that I didn’t realise I’d be looking for something cloudy in a 5 litre container…

There’s not a great deal to see in Arica, but enough to keep me entertained for a few days. I went a little out of town to visit a museum on the site of where the world’s oldest mummies were found which was interesting, although the displays of the mummies themselves was a little macabre [6]. Barbecue in the evening and an attempt at making Terremotos, the latter required some work as the wine used to make isn’t particularly easy to find – it didn’t help that I didn’t realise I’d be looking for something cloudy in a 5 litre container…

Then it was time to leave again. North and then east, skirting the Peruvian border and rapidly gaining height until I arrive at Putre, a small and quite picturesque town at around 3,500m. A cold night, a good breakfast and then off after finding 5 litres of fuel from a shop in town, which would be enough to get me to Patacamaya, the first town I thought I’d have a decent chance of finding a petrol station.

Then it was time to leave again. North and then east, skirting the Peruvian border and rapidly gaining height until I arrive at Putre, a small and quite picturesque town at around 3,500m. A cold night, a good breakfast and then off after finding 5 litres of fuel from a shop in town, which would be enough to get me to Patacamaya, the first town I thought I’d have a decent chance of finding a petrol station.It’s with some sadness that I leave Chile for the last time this trip (hopefully I’ll be back) and enter Bolivia. This time the customs process takes significantly longer and requires much more paperwork, including photocopies of documents, a trip to another office and the VIN of the bike being checked for the first time since the bike first arrived in Argentina – why it was so different from crossing from Argentina I have no idea, but the fact that it was at around 4,000m didn’t help.

Finally on my way and I see a petrol station, but they won’t sell me any fuel as they said they didn’t have the paperwork to sell to foreigners (if you have foreign plates you pay a different (significantly higher) price for fuel. Not too worried I carry on and am taking a photo when a car pulls up. They’d seen me at the petrol station and offered to sell me some fuel. I followed them to a small building a couple of hundred metres off the road and buy 3 litres of fuel from them, then carry on. The road is in good condition and I make good time to Patacamaya and refuel properly. Then the road worsens, with lots of roadworks, and the resulting diversions onto tracks, so when the tarmac is good I speed up to make up time (I want to arrive in Oruro in daylight), which is when I become aware of the first speed gun that I’ve seen in all of Latin America so far [7]. After that I slow down to ensure I’m definitely below the speed limit, but that, and the frequent road works, means it’s dark by the time I arrive in Oruro, and then a lack of road signs means it takes longer to find somewhere to stay, but eventually I find a room in a hostel and a secure car park for Lena and grab some food.

Finally on my way and I see a petrol station, but they won’t sell me any fuel as they said they didn’t have the paperwork to sell to foreigners (if you have foreign plates you pay a different (significantly higher) price for fuel. Not too worried I carry on and am taking a photo when a car pulls up. They’d seen me at the petrol station and offered to sell me some fuel. I followed them to a small building a couple of hundred metres off the road and buy 3 litres of fuel from them, then carry on. The road is in good condition and I make good time to Patacamaya and refuel properly. Then the road worsens, with lots of roadworks, and the resulting diversions onto tracks, so when the tarmac is good I speed up to make up time (I want to arrive in Oruro in daylight), which is when I become aware of the first speed gun that I’ve seen in all of Latin America so far [7]. After that I slow down to ensure I’m definitely below the speed limit, but that, and the frequent road works, means it’s dark by the time I arrive in Oruro, and then a lack of road signs means it takes longer to find somewhere to stay, but eventually I find a room in a hostel and a secure car park for Lena and grab some food.I don’t sleep very well and wake up the next morning with a headache that stays for the entire day and self-diagnose myself with mild altitude sickness (symptoms are essentially the same as a hangover but worse at night). I was planning on heading to Potosi the next day, but given that it’s even higher (around 4,000m) I decided it would be more sensible to head to Sucre (around 2,500m) and spend a bit of time there re-acclimatising, and then head to Potosi. There were three different routes I could take to Sucre. The most direct was route 6, but most of the 350km or so would be ripio, whereas the longer route south, via Potosi, was all tarmac (and the route north was all tarmac but a lot longer). Eventually I decided to take the “boring” southern route. I wasn’t confident that I’d be able to do route 6 in a day and didn’t want to be forced to camp at an even higher altitude (the route went about 4,000m for a lot of the time). As it was after an uneventful ride, I arrived in Sucre shortly after sunset and found a hostel with a garage.

Sucre is where Bolivia was established as a country and is still the official capital [8], although it no longer has the seat of Government (which is in La Paz) and has a lot of fine colonial buildings. In the end I spend just over a week there, taking in the sights at a leisurely pace, reading, trying to catch up on the blog and a bunch of other admin. And Sucre is a nice place to spend time – being lower it’s warmer, hot even during the day and not that cold at night – like a good day in an English summer. There are a few universities and lots of Spanish language schools, so as well as the local student there are quite a few foreigners here for a while doing a language course, which gives the place a different vibe to some of the more transitory places I’d been to in Bolivia like Tupiza and Uyuni. As well as the sights in town (like the Casa de la Libertad, MUSEF, Recoleta and countless churches) there is a cement factory quarry about 10km out of town which is worth a visit. They were extracting limestone from the quarry when it sheared down a fault line, exposing a near vertical cliff face with more than 5,000 fossilised dinosaur footprints. The face had originally been a lake which had dried, the footprints had set, then fossilised and then geological activity concertina-d the rocks, making it vertical. It’s on the other side of a small valley and I wish I’d brought my binoculars, but you could still clearly see the tracks of the different dinosaurs, each of which had been identified and from the different prints it was possible to estimate the different sizes.

Sucre is where Bolivia was established as a country and is still the official capital [8], although it no longer has the seat of Government (which is in La Paz) and has a lot of fine colonial buildings. In the end I spend just over a week there, taking in the sights at a leisurely pace, reading, trying to catch up on the blog and a bunch of other admin. And Sucre is a nice place to spend time – being lower it’s warmer, hot even during the day and not that cold at night – like a good day in an English summer. There are a few universities and lots of Spanish language schools, so as well as the local student there are quite a few foreigners here for a while doing a language course, which gives the place a different vibe to some of the more transitory places I’d been to in Bolivia like Tupiza and Uyuni. As well as the sights in town (like the Casa de la Libertad, MUSEF, Recoleta and countless churches) there is a cement factory quarry about 10km out of town which is worth a visit. They were extracting limestone from the quarry when it sheared down a fault line, exposing a near vertical cliff face with more than 5,000 fossilised dinosaur footprints. The face had originally been a lake which had dried, the footprints had set, then fossilised and then geological activity concertina-d the rocks, making it vertical. It’s on the other side of a small valley and I wish I’d brought my binoculars, but you could still clearly see the tracks of the different dinosaurs, each of which had been identified and from the different prints it was possible to estimate the different sizes. On another day I rode out to Maragua, an extinct volcano about 60km from Sucre. The first 30km being good tarmac, and then it changes to ripio and roads that zig zag up and down hills pas some stunning views. The map that I was using was apparently a little out of date, as the route it took me involved going down a path that obviously hadn’t been used, then a river crossing and tracing the river up the valley before re-joining a much better quality road further up (on the way back I found out that a new road had been cut through the hillside, making the old road obsolete). Maragua wasn’t a particularly pretty town but it was in quite a spectacular location in the centre of a large caldera with green striped hillsides on one side and then a valley on the opposite (eastern) side. I stop to take some photos and have some of the sandwiches I’d packed or myself and then head back onto the main road.

On another day I rode out to Maragua, an extinct volcano about 60km from Sucre. The first 30km being good tarmac, and then it changes to ripio and roads that zig zag up and down hills pas some stunning views. The map that I was using was apparently a little out of date, as the route it took me involved going down a path that obviously hadn’t been used, then a river crossing and tracing the river up the valley before re-joining a much better quality road further up (on the way back I found out that a new road had been cut through the hillside, making the old road obsolete). Maragua wasn’t a particularly pretty town but it was in quite a spectacular location in the centre of a large caldera with green striped hillsides on one side and then a valley on the opposite (eastern) side. I stop to take some photos and have some of the sandwiches I’d packed or myself and then head back onto the main road.

On the way I decide to try and find a way to the rock paintings of Incamachay. The map that I have has a road which Incamachay is on, but this road didn’t link to any other road. I get as close as I can to one end and find a trail that heads off the main road in the right general direction and follow it for a short while, then the track deteriorates significantly. I walk up to a high point to take in the view (which is amazing), but can’t see where the track goes to, so decide to head back to Sucre rather than explore further (and risk getting stuck on a goat track in the middle of nowhere as it’s getting dark).

I decide that I need to get moving again and load the bike up and head to Potosi, which is only a couple of hours drive down the road, and all tarmac. After a few attempts I find somewhere to stay where I can securely park the bike in the hostel annex, which involved riding up a combination of planks that made it more like something from xxxx. I parked Lena at the same time as two Germans who were travelling (together, with their luggage) on a 125cc bike from Paraguay. Fair play to them but it’s not the bike that I’d choose to do it on.

Potosi is the highest city in the world and famous for being a silver town and is dominated by the Cerro Rico. This previously volcanic hill had veins of 80% pure silver when it was found in the Sixteenth Century. The Spanish soon learnt of it and for the next ~300 years the hill bankrolled the Spanish Empire, created a global currency and filling the pockets of the pirates and privateers that harried the Spanish fleets transporting it back to Europe.

The mine is still working and although it is now far less productive, still drives the economy of the town – as far as I could see there wasn’t any business there that wasn’t in some way dependent on the income the mines produced. At the hostel I met a French guy who told me about his experience of visiting the mine on a tour that morning, which involved the warning “some of the miners might want to fight you, if they do, you have to fight them” which made it apparent that this was not going to be like the mine visits you can do in Wales. I went the next afternoon and after being kitted out in jacket, trousers, wellie boots and a helmet with lamp we headed off to the miners market. Here we bought “gifts” for the miners, things that helped the miners in their work and meant that tours like ours are, if not welcomed with open arms, are at least tolerated. Gifts included juices (inside the mountain it can get very hot, and the work is very physical, and at 4,000m), dynamite (the sale of TNT, potassium nitrate and fuses is not controlled in Potosi, so anyone can buy it) and 96% (NB, not proof) drinking alcohol. We were told that the alcohol is only drunk on Fridays (it was a Wednesday) so we didn’t buy any, but we were able to try a sample [9]. The only other thing the miners take into the mountain with them, other than their tools, is a bag of coca leaves. They don’t eat because of the dust, and apparently they haven’t discovered Cornish Pasties [10]. Then we go the one of the processing plants that takes the raw materials from the mines. The mines are cooperatives, meaning that the miners within the cooperatives are essentially self-employed. The processing plants are privately owned, but are very far from sophisticated. In basic buildings on the hillside they take in the rocks at the top where it’s graded to determine the average silver content (and therefore the price that will be paid). It’s then pulverised, washed and then sent into baths of a mix of noxious chemicals that cause the silver to form bubbles on the surface, which is then scraped off and sent to be dried, packaged and then sent off to Chile and Peru for onward shipping to smelting centres where the actual silver is made (all of the smelters in Potosi have now closed). The whole operation has an incredible Heath Robinson feel to it, except that the chemicals being used are incredibly toxic (cyanide for example) making the place feel like an incredibly unhealthy environment to work in, even passing through for only a few minutes.

Then up the mountain to the mine entrance

Notes - to be fleshed out shortly

Potosi

Sucre

Notes:

1. Possibly TMI, but this attempts to be an honest blog and anyone who says they've been travelling for a decent amount of time in interesting places and tells you they haven't had a stomach upset is lying. I think the cause of this was either related to the 24 hour bug I'd had in Lago Colorago, or was from the lunch I had when I arrived in San Pedro - I'd foolishly broken my own rule of never eating something with shellfish in it (prawns in this case), when you can't see the sea.2. a ghost town from the nitrate mining days).3. Arturo Prat’s ship that was sunk by the Peruvian navy in Iquique harbour.4. If you’ve seen the Top Gear Bolivia special, it could have been the sight of the final drive down the hill to the Pacific although I didn’t see the remains of a three-wheeled Landcruiser.5. Not helped by the fact that as I filled up the bike at a petrol station I met two Chilean motorcyclists who were making their way down from Colombia. They’d been on the road for 6 months, and I’d been riding for about 5 and a half, so we decided that we’d met at around the half way point!6. The mummies which had been found near San Pedro had been removed from display there for ethical reasons.7. I’ve written more about the experience here but am not going to publish it until I’ve left Bolivia for good, just in case…8. Good pub quiz question as most people will say La Paz, although apparently they’re going to vote on it so in a few years time the answer may be different.9. It was a lot smoother than I expected, although the “warming” alcohol feel on the throat lasted longer than anything I’ve ever drunk before, as could be expected. In contrast, where I’d spilt some of the alcohol on my fingers while making an offering to Pachamama, were colder – you could feel the alcohol evaporating off.10. Although they do have Saltenas, which are very similar, albeit much juicier so probably not ideal for a mine environment.

Sunday, 13 July 2014

Leg 8 - Uyuni to San Pedro de Atacama

Route summary: Uyuni, Salar Uyuni, Isla Incahuasi, San Juan, Laguna Colorado, San Pedro de Atacama.

Days: 5

Zero mileage days: 0

Distance (point to point): 307km

Distance (driven): 668km

Inefficiency factor (Driven/P2P): 2.18

Avg. speed: 134km/day

Click here for detail.

The idea for the next leg came to me when I was around

Salta. I wanted to go to Uyuni, and I also wanted to see San Pedro and some of

the remaining northern bits of Chile, but the problem of the Andes reared it's head again and I dislike riding over the same roads more than once. I’d read in a book about a route from Chile to San Pedro de Atacama,

which would make the link (it's one of the routes that the tour companies in Uyuni run). The only obstacles to doing this were:

- Tour groups do it using Toyota Landcruisers - for a reason, the route covers some pretty awful terrain.

- The book suggested doing it in a group of at least 3 bikes - I ride alone [cue dramatic music / black and white shot of me gazing wistfully into the distance], or I don't have enough friends...

- The book also talked about needing to arrange fuel drops.

- People coming off tours said that the temperature in the area was getting down to -25°C overnight. Apart from the fact that I wasn’t sure my sleeping bag, even the new one, would be effective at that temperature, I wasn’t sure what it would do to Lena. She’s water cooled and although the radiator has anti-freeze, I didn’t know at what point even that would give up.

- The mapping I had was rubbish - the GPS mapping I had for Bolivia was so useless they might as well put "here be dragons" in big print across the screen; the paper maps I had of Bolivia were too large scale to be of any use; the map of the Salar and south that I'd bought in Tupiza seemed to be missing places and roads (and as I found out later was next to useless). So the only real guide I had was the instructions from the book.

I don’t plan to spend long in Uyuni, just the one night

ideally so once I’ve got somewhere to stay and I’ve unloaded the bike I head

back out to have a look at the train cemetery a little out of town. Initially

all I see are a few carriages, some on their side and am not very impressed,

but a little further on are some big engines, in varying states of

disintegration. One has been turned into a swing, while the bogeys of another are

lying in the sand like a dead lift from a World Strongest Man competition.

It was starting to get close to sunset so I headed back into town and find a

carwash – I want the bike clean and greased before I head out into the salt

flats and although I had her cleaned in Humahuaca she’s already filthy again.

I’ve also noticed that the corrugations on the ride in have broken a bracket on

the skidplate and while I’m having the bike washed I ask the driver of a tour

4x4 where he’d recommend to get some welding done (I’m getting some pretty

niche Spanish it has to be said) and get an address off him. I also get the

location of a garage for fuel, but don’t fill up yet, I want to brim the tank

just before I leave, fuel is going to be one of the big unknowns on the next

leg. Then it’s back to the hostel, some food and an early night. When it gets

dark it gets cold pretty quickly and so I’m glad that the dorm is full, more

bodies means more heat and it was a pretty comfortable night.

I don’t plan to spend long in Uyuni, just the one night

ideally so once I’ve got somewhere to stay and I’ve unloaded the bike I head

back out to have a look at the train cemetery a little out of town. Initially

all I see are a few carriages, some on their side and am not very impressed,

but a little further on are some big engines, in varying states of

disintegration. One has been turned into a swing, while the bogeys of another are

lying in the sand like a dead lift from a World Strongest Man competition.

It was starting to get close to sunset so I headed back into town and find a

carwash – I want the bike clean and greased before I head out into the salt

flats and although I had her cleaned in Humahuaca she’s already filthy again.

I’ve also noticed that the corrugations on the ride in have broken a bracket on

the skidplate and while I’m having the bike washed I ask the driver of a tour

4x4 where he’d recommend to get some welding done (I’m getting some pretty

niche Spanish it has to be said) and get an address off him. I also get the

location of a garage for fuel, but don’t fill up yet, I want to brim the tank

just before I leave, fuel is going to be one of the big unknowns on the next

leg. Then it’s back to the hostel, some food and an early night. When it gets

dark it gets cold pretty quickly and so I’m glad that the dorm is full, more

bodies means more heat and it was a pretty comfortable night.

The next morning I go round to the welders and even though

the say they don’t do bikes I say that I can take the parts that need welding

off the bike and they relent so I go back with the bike and they weld the

skid-plate perfectly, and also get them to weld the camel-toe onto my side stand

(the fixtures that came with it having bent out of shape long ago, meaning it

kept falling off).

By now it’s lunchtime, but I’m not planning on going far, so

not too worried. Load up, fuel up and then head off. It’s initially north for

about 20km and then a road goes west out of Cochani. The town soon comes to an end

and then the road runs into the Salar. My destination that night was one of the

salt hotels on the salar (there are three). It’s not a cheap night but you get

to sleep on the salt flat in a hotel made entirely out of the stuff. I got

there just as the Argentina semi-final had started, so had the rather surreal

experience of watching the game on a big flatscreen TV while the sun set over

the salar outside.

By now it’s lunchtime, but I’m not planning on going far, so

not too worried. Load up, fuel up and then head off. It’s initially north for

about 20km and then a road goes west out of Cochani. The town soon comes to an end

and then the road runs into the Salar. My destination that night was one of the

salt hotels on the salar (there are three). It’s not a cheap night but you get

to sleep on the salt flat in a hotel made entirely out of the stuff. I got

there just as the Argentina semi-final had started, so had the rather surreal

experience of watching the game on a big flatscreen TV while the sun set over

the salar outside.

At the hotel I met a Spanish cyclist who’d just come the

opposite direction to the one I was planning and looked exhausted. We talked

maps and GPS waypoints and he gave me a printout which was to prove to be very

helpful. The only other information I had was the verbal description from the book and some waypoints I'd taken from the book and converted into Lat and Long for the GPS using GoogleMaps. However, that only told me roughly where I was aiming for, not the route the road took - and as I've demonstrated before, I'm not a Dakar rider and the straight line route doesn't always work so well for me.

He also told me about some better mapping for Bolivia. I wasn’t able to put the mapping onto my GPS though, I was missing

a key piece of software and didn’t have time to download it in the hotel. I

wish I had, it would have made the next 4 days a bit easier and would have

reduced the background worry when you’re not entirely sure where you are [1].

As a result of this I ended up leaving later than planned

onto the salt flats. Shortly after getting onto the flats there’s a memorial

commemorating a group of tourists who were killed in a vehicle crash, it also

acts as a warning to others. At this I see a group of four motorcyclists who

have stopped. They’re Chilean riders on a road trip and are keen to go to one

of the islands on the salar but none of them have a GPS. I volunteer to lead them out and after a short ride we come across a Dakar statue and get some photos, then it's off to the island. I'd read that you get great grip off the salt and moved off the beaten paths to see what it was like, and it was amazing. A slight crunch as you crossed the small salt walls and you're soon laughing uncontrollably into your helmet. The other riders soon follow me off the trails and then there are five of us, hooning across the salt flat, occasionally in formation, some slowing and others cruising past, and stack load of photos being taken. It was honestly some of the most fun riding I've done, on a massive, white, playground. You'd see a car parked up, in the middle of nowhere, with the boot open and a table set up for people to have an early lunch and like hooligans you'd see how close and how fast you could buzz them. Childish but fun, and they seemed to enjoy it as well.

As a result of this I ended up leaving later than planned

onto the salt flats. Shortly after getting onto the flats there’s a memorial

commemorating a group of tourists who were killed in a vehicle crash, it also

acts as a warning to others. At this I see a group of four motorcyclists who

have stopped. They’re Chilean riders on a road trip and are keen to go to one

of the islands on the salar but none of them have a GPS. I volunteer to lead them out and after a short ride we come across a Dakar statue and get some photos, then it's off to the island. I'd read that you get great grip off the salt and moved off the beaten paths to see what it was like, and it was amazing. A slight crunch as you crossed the small salt walls and you're soon laughing uncontrollably into your helmet. The other riders soon follow me off the trails and then there are five of us, hooning across the salt flat, occasionally in formation, some slowing and others cruising past, and stack load of photos being taken. It was honestly some of the most fun riding I've done, on a massive, white, playground. You'd see a car parked up, in the middle of nowhere, with the boot open and a table set up for people to have an early lunch and like hooligans you'd see how close and how fast you could buzz them. Childish but fun, and they seemed to enjoy it as well. |

| Incahuasi, one of the Isla Pescadores - note the Cessna which made a flying visit |

|

| The salar from the island |

- I'd headed at least 6 km west, so even the bearing to the waypoint I'd created would take me on a course tracking to the east of the route in the book.

- The book was wrong, the course from the island you need to take is about SSE, so the course I was on was taking me even further west of where I needed to be.

- In between me and the right waypoint was an area of the salar called Pio Pia, although I didn't know this until the next morning.

|

| The mess left after getting Lena out of the salt/mud hole, note that the tracks in don't lead into the ones out |

|

| And obstacle number 2, deep gritty sand |

Back onto the salar and a return to the crispy, slimy nightmare. The back wheel starts to fishtail, I slow down which helps a bit, then it starts up again, I lose the front wheel and the bike goes down. I'm quickly up and get the bike up pretty fast as well (the adrenaline helps lift the bike and it's also a good way to prove you haven't broken anything!) and then realise that left hand pannier has been ripped off the bike, breaking the bracket at the base of the pannier. Move the bike onto more solid ground and make sure I've got all of the bits of pannier before fixing it back to the bike (the top bracket still holds although it's not the most rigid connection, I'll have to fix it properly later).

Back onto the salar and a return to the crispy, slimy nightmare. The back wheel starts to fishtail, I slow down which helps a bit, then it starts up again, I lose the front wheel and the bike goes down. I'm quickly up and get the bike up pretty fast as well (the adrenaline helps lift the bike and it's also a good way to prove you haven't broken anything!) and then realise that left hand pannier has been ripped off the bike, breaking the bracket at the base of the pannier. Move the bike onto more solid ground and make sure I've got all of the bits of pannier before fixing it back to the bike (the top bracket still holds although it's not the most rigid connection, I'll have to fix it properly later).By now it's starting to get dark. San Juan isn't happening today and I decide to head back to the island I'd been on earlier and see if I can spend the night there. As I ride I'm thinking through the different options - if I can stay on the island, I should have enough fuel for me to get to either Villa Colcha K or San Juan (both places I've heard you can buy petrol). If I have to go back to the Salar hotels or Cochani I'll need to get more fuel in Colchani or Uyuni and effectively start again tomorrow. It becomes bitterly cold on the ride north back to the island and I realise quite how far off to west I was, but soon the salt turned back to the stuff I'd been enjoying earlier in the day and I got back to the island. There I asked if there was somewhere I could stay, explaining that I'd got a bit lost, and he showed me to a room, simple, but pretty windproof, with a mattress and blankets. He then asked if I wanted some food - you have no idea how happy I was. I met a French cyclist who was also staying, he'd planned on camping but after seeing the room decided to join me and take the other mattress. It was here that I learnt that I'd ventured into Pio Pia, where 4x4's have been known to get bogged in to such an extent it's taken days or weeks to recover them. I felt lucky that I'd only had a bike to lift out. And even though I'd had a pretty tough afternoon, I still went to bed with a smile on my face.

|

| Southern cross top centre, which means south is about half-way along the bit of island in the foreground |

|

| Now with added straps |

|

| Finally found, the road off the salar |

|

| Decisions, decisions |

This bears east and then bends back to the south and then hits the raised salt road that I've been looking for. Along this are occasional hot springs, creating green pools by the side of the road. The salt road becomes a gravel road and I turn away from the salt flats for the last time. A little sad - the previous morning had been great fun - but with some relief that I was, at least for now, on the right road. I followed the road south, trying to keep to the slightly higher paths where more than one existed on the grounds that this was less likely to be sandy, and arrive in Villa Colcha K on the second attempt (the first route in required crossing a very muddy water crossing, the second route had a water crossing as well but one that looked shallower, if longer). I ask where I can buy fuel and am pointed towards a small shop, basically a door and someone's front room. They ask me how much I want and I go for 10 litres which is duly brought out in a mixed bunch of plastic bottles. Get something to drink, have a short wander around the town before heading on.

|

| Road spotting |

|

| Did I tell you how much I love sand? |

There's not much to the village/town. I ask around for fuel but it looks like the only person that usually sells it is out of town, although someone kindly offers to sell me some if I can't find them. Someone returns later that evening and when I knock on the door she tells me to come back tomorrow morning early. I only want about 5 litres but it seems to make sense to get it when I can.

There's not much to the village/town. I ask around for fuel but it looks like the only person that usually sells it is out of town, although someone kindly offers to sell me some if I can't find them. Someone returns later that evening and when I knock on the door she tells me to come back tomorrow morning early. I only want about 5 litres but it seems to make sense to get it when I can.Up the next morning at around 6 to get fuel, breakfast and then head off. When I've told people that I wanted to travel from San Juan to Lago Colorado in a day they tended to suck in their teeth and tell me it would be a long day, so an early start seemed the right thing to do.

Asking at the hostel the way to xxx, the next village on my route, I'm told to head on the main road out of town heading WSW. This is not the way that the book says, but is in approximately to same direction so I'm assuming they'll meet up at some point. The book says that I follow a railway line along and after 20 minutes, still no railway. I take a couple of guesses on the rout, which takes me kind of in the right direction and eventually I find that I'm arriving at the village, however I've taken a different (and about 50% longer) route. That said, the ride was all along pretty decent condition ripio roads.

Follow the railway line (which I've now found) out of the hamlet until, as foretold by the book (it worked for once), the road started to peel away to the left. Another car was parked in the same area, so I double checked with the driver that I was going in the right direction before heading on, across as small salar and then up the hill on the other side. I stuck to the main track but the tracks multiplied so I tried to stuck with the one in the best condition, heading in approximately the right direction [2]. And then, to my right I spied road signs, which I hadn't seen in a long time. I picked tracks as best I could to get over towards what I could now see was a maintained (but still ripio) road, and then, typically, about 50m from joining what was looking like a smooth, gravel road (after having had anything but), I dropped the bike, for the first time that day, but unfortunately not the last. Get it upright and head on, a little embarrassed onto the road. It wasn't tarmac but it was a whole lot nicer than anything I'd been riding on since first thing that morning and I just had my fingers crossed that it would last for a while.

|

| More strapping |

|

| ...and a bit of lashing |

|

| Finally, Laguna Canapa, only another 6 to go... |

Finally, everything's back together and I ride down to Laguna Canapa and try and admire the view. It's about midday and I ask a driver how long it should take to Lago Colorado and I'm told about 4 hours, with stops at the sights on the way. I know that I'm not going at the same pace as the 4x4s but figure I should still be able to make it by nightfall. Then it's round lakes, over hills to other lakes, then more lakes.

Finally, everything's back together and I ride down to Laguna Canapa and try and admire the view. It's about midday and I ask a driver how long it should take to Lago Colorado and I'm told about 4 hours, with stops at the sights on the way. I know that I'm not going at the same pace as the 4x4s but figure I should still be able to make it by nightfall. Then it's round lakes, over hills to other lakes, then more lakes.The road varies between poor and occasionally awful, but the scenery is nice. Then the road gets higher and opens out into a fairly broad valley with tracks cut through the stony, gravelly ground by the 4x4s. Hundreds of tracks, all with their own channels and the going gets slow again. Any speed at the bike kicks into a side and goes over, and for long sections I'm forced to paddle my feet as if I were riding through sand. Third gear is a distant memory and second only happens occasionally. I can feel myself getting tired. Each time the bike goes over it takes longer to steady my breathing long enough to lift her up again. The number of cars going past - always on the "other" side of the valley - which makes me think there has to be an easier road somewhere, seems to diminish as the afternoon wears on, which is worrying. The cars acted as a positive check that I was going in the right direction, and given that they were heading somewhere to sleep before nightfall, I could reasonably expect to find civilisation at some point.

|

| Arbol de Piedra |

|

| The last run in, a couple of kilometres so maybe half an hour... |

|

| Sunset... |

|

| ...and moonrise over Lago Colorado |

|

| Dawn |

The first 6km were horrible, like the worst terrain of the previous day and the thought of another 120km of this to the border didn't bear thinking about. Fortunately for my sanity it improved and although still difficult, I felt like I was making progress.

The first 6km were horrible, like the worst terrain of the previous day and the thought of another 120km of this to the border didn't bear thinking about. Fortunately for my sanity it improved and although still difficult, I felt like I was making progress. I then saw two tour vehicles and decided to follow them as best I could. One had parked up at a pass, next to some snow fields and I asked the driver the way to the Termas. He said I was going in the right direction but the geysers were first, I asked if I could follow and he said that was fine. So I followed him to the geysers and then on to a lake, at the edge of which were some hot springs. A quick dip and back onto the bike.

I then saw two tour vehicles and decided to follow them as best I could. One had parked up at a pass, next to some snow fields and I asked the driver the way to the Termas. He said I was going in the right direction but the geysers were first, I asked if I could follow and he said that was fine. So I followed him to the geysers and then on to a lake, at the edge of which were some hot springs. A quick dip and back onto the bike.

The car I was following is staying and so I head on, past the Desierto de Dali (so named for the surreal colourings and rock formations), coming to the shores of Laguna Verde and Laguna Blanca. Laguna Verde is stunning, it is genuinely green, with an amazing volcano as backdrop. Unfortunately it was a bit windy, kicking up white horses on the lake so the photos don't show it in all its glory.From the bicycle map I had I'd seen that there was a route between the two lakes, but no vehicles seemed to have used it in a while so I decide to take the other route, circumnavigating Laguna Blanca and then passing through the ranger station. The border, a lone building in the middle of nowhere, was the next stop, about 5km away.

I get to the border and the guy working there starts talking about "Aduana" (customs), telling me that he can only give me an exit stamp, he can't stamp my bike out, and that I need to turn around and ride 80km back to where I can get a stamp. However, he can't tell me where I can get this stamp (the name of the village / town / city) and he doesn't have any phone or radio contact with anywhere else to find out. Eventually someone with better spanish comes along, says everything that I did and the guy relents, takes my bike import form, stamps my passport and lets me leave. I get out of there as quickly as I can, I just want to get to tarmac now (only another couple of kilometres) and then 45km to San Pedro and the Chilean border.

I get to the border and the guy working there starts talking about "Aduana" (customs), telling me that he can only give me an exit stamp, he can't stamp my bike out, and that I need to turn around and ride 80km back to where I can get a stamp. However, he can't tell me where I can get this stamp (the name of the village / town / city) and he doesn't have any phone or radio contact with anywhere else to find out. Eventually someone with better spanish comes along, says everything that I did and the guy relents, takes my bike import form, stamps my passport and lets me leave. I get out of there as quickly as I can, I just want to get to tarmac now (only another couple of kilometres) and then 45km to San Pedro and the Chilean border. I arrive in San Pedro with (I thought) an hour until kick-off of the World Cup Final. It turns out the Argentinian person I'd met that morning had the kick-off time wrong and I arrived just as the match was starting. Eventually get some very reluctant (but remarkably quick) border and customs people out to help me and I'm in to town, find some food, somewhere to stay and store Lena and crash, almost oblivious to the revelry of the celebrating Germans.

I arrive in San Pedro with (I thought) an hour until kick-off of the World Cup Final. It turns out the Argentinian person I'd met that morning had the kick-off time wrong and I arrived just as the match was starting. Eventually get some very reluctant (but remarkably quick) border and customs people out to help me and I'm in to town, find some food, somewhere to stay and store Lena and crash, almost oblivious to the revelry of the celebrating Germans.

Lessons from the Uyuni to San Pedro ride:

- Have decent mapping. Nothing saps confidence like not being sure you’re ging in the right direction, especially if that direction involves awful roads. The GPS mapping that I’d been using in Argentina and Chile was very good, and road signs well marked. In Bolivia the GPS mapping became very sparse (it doesn’t have all the major towns on it and is missing at last some of the tarmac roads, let alone the major ripio roads) and paper maps are of pretty poor quality.

- Reset your Distance / Speed / Time calculation. Which usually means not trying to go as far and starting earlier.

- Ask other people (and follow them if you can).

- If there are people, there is very likely to be fuel and water, although both might be expensive.

- Make sure you know where the border is, from both an immigration and a customs perspective.

Notes:

1. See here for a link to the mapping. It didn’t help that my laptop had started to play up. I think it was also affected by the road from Tupiza and was taking hours (literally) to start up.

2. Around this time I started to get a bit philosophical (no doubt a result of lack of oxygen, I was around 4,500m now), comparing riding along some of these crappy tracks to life in general. Sometimes you pick the track, but more frequently because of momentum and limited steering, the track choses you, and then all you can do is hold on, hope there weren't any big rocks and try not to fall off.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)